Bismuth - an Investigation. Part One.

Bismuth has been on my research list for quite a while now, and I finally got round to studying it in more detail.

Bismuth is a relatively soft metal that’s not too difficult to get a hold of - it’s actually mined here in Bulgaria, so sourcing it was super easy.

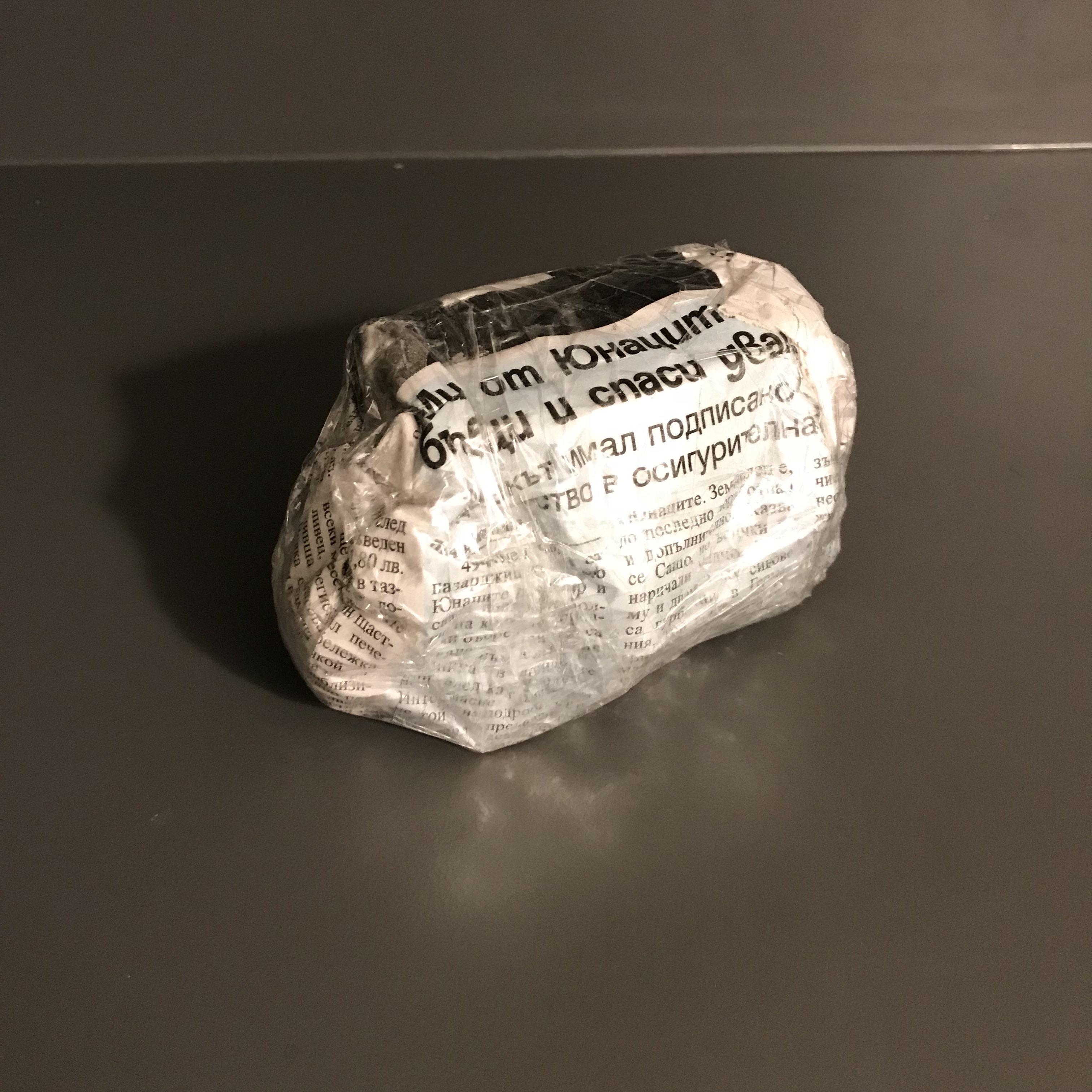

I ordered 3 kilos of bismuth (around 6 and a half pounds) online, and got the following package in the mail a day later:

Sooo, yeah, that was a pretty dodgy start of my project, but things get a lot better. I promise!

This will be a three part series. The first one will cover some of the general studies I’ve done on bismuth, the second will focus on a few key features of the metal, and the final one will incorporate it in a project.

Scope

When it comes to metals, there are a number of different factors to measure and take into account. Here are some of the common ones:

- physical strength

- metallic shine

- thermal conductivity

- electrical conductivity

- chemical properties

- melting/boiling point

- magnetic properties

- oxidation

- hazardous state (toxicity and radioactivity)

- reaction with other metals (alloys and amalgams)

The list above is more or less a staple when it comes to studying elements, and the result set gives a very good evaluation of what’s considered the most important quality of all - usefulness.

Not all elements are created equal - some have better strength, others might be more conductive, but it all boils down to what you can do with the ‘skill set’ of a metal.

Physical strength and metallic shine

Bismuth looks rather unimpressive in its raw form - it has medium shine, and didn’t score any better in the strength department either - some of it chipped after I whacked it with a chisel a few times:

The results of this test are worse than copper or aluminum - both are not very hard, but dent instead of chip when damaged.

Conductivity

Thermal conductivity seems pretty low - I headed the piece of bismuth from one side for a few minutes, but the heat did not seem to distribute evenly throughout the whole block.

Bismuth is not a great conductor either. I measured my sample with a multimeter, and its resistance was way higher than some other metals. It’s no copper.

Chemical properties - alloys and amalgams

An alloy is a mix of two or more metals in specific proportions, though sometimes non-metallic compounds are used as well. Materials are smelted, mixed and then cooled down to produce a solid that has the characteristics of its components. Common examples are brass, pewter, and steel.

An amalgam is a mix of mercury (the only metal that’s liquid in its inert form at room temperature) with other metals. Classic examples for amalgams are old school dental fillings. They’re a mix of 50% mercury with silver powder and sometimes tin or zinc.

I don’t have the necessary equipment to make alloys at home or my shop, so decided to do some online research instead.

However, it seems that bismuth is commonly used by construction companies to secure road signs and electrical poles. Unlike most other elements, bismuth shrinks when melted, and expands after cooling down. So pouring bismuth based alloys around the base of a long tall pole would give it extra strength and maker it harder to displace. Gallium is another metal that exhibits the same property, but it’s super low melting point of around 30 °C is a turn off for almost any industrial use.

Bismuth is kind of sort of maybe radioactive

Right. And that’s actually a relatively new discovery. Although bismuth is technically radioactive, its half life is millions of times longer than the age of our planet. That’s way too long to be considered dangerous, so bismuth’s alpha decay is widely considered harmless.

Regardless of what I mentioned, bismuth is not toxic

It’s actually the main ingredient in Peptobysmol - that pink gooey syrup that’s prescribed for stomach aches. I haven’t had the need to use it myself, but when it comes to gastric medicine, things usually go like this - too little has no effect, and too much can make you crap your pants.

Bismuth has a very low melting point

One of the defining characteristics of bismuth is its stupidly low melting point - around 270°C (~ 500°F). That’s REALLY low for a metal. In comparison, copper melts at around 1000°C and iron liquifies at 1500°C.

This means that it’s relatively easy to smelt bismuth at home - all you need is an old stainless steel pot and a stove.

A few words about safety

Even though bismuth is not toxic, melting it can be rather dangerous.

First are the fumes. They start forming when bismuth turns liquid, and are the result of it reacting with air. Metals usually have impurities in them, and the first couple of smelts form a thick layer of slack that can also release dangerous gasses. It’s never a good idea to inhale them, especially indoors. I made sure to wear a respirator and turn the kitchen hood all the way up.

It also goes without saying that any piping hot liquid can cause third degree burns, so wearing extra protection like thick welding gloves and a face mask are a must.

To ensure my kitchen area would not get damaged during the melting process, I covered everything in two sheets of aluminum foil. So in the event of an accidental spill, I could just lift the foil and let the liquid metal solidify without burning anything.

This concludes part one of my bismuth journey. Stay tuned for part 2 where I’ll show you how the smelting process went and also explore a couple other properties which were not covered in this article.